The Sudden Collapse of ISG Ltd

On 19 September 2024, ISG Ltd was the UK’s 6th-largest construction firm. It commanded a £2.2 billion turnover. Its portfolio spanned sectors from education to healthcare. ISG boasted high-profile clients like Apple, Google, and Barclays. Touted as a cornerstone of the UK construction industry, it was an active participant in 69 government schemes, including projects like the Ministry of Justice’s prison expansion programme.

By the next day, 20 September 2024, ISG was in administration. The National Access & Scaffolding Confederation (NASC), a UK construction industry trade group, expressed deep concern after ISG’s collapse, noting that many subcontractors now face significant uncertainty. Firms in this sector, already operating on tight margins, are vital to UK construction. Many now have equipment tied up at multiple sites and face severe cash flow problems.

Construction company ISG Ltd filed for administration in September 2024. (Image courtesy of Administration List.)

ISG’s ruin was rooted in financial issues that were kept from the public eye. In 2022, when two large construction projects were cancelled, ISG lost revenue. The board told shareholders, customers, and suppliers that the company was still viable and would continue to be so. Senior management tried to curb losses with layoffs, which worsened the problems. Even as specialist publications like Construction Enquirer and Building Magazine investigated ISG’s missteps, the business kept painting an image of a firm in complete control of its operations. Nobody outside ISG predicted the eventual outcome. Due mainly to their PR operations, they sustained a reputation as a high-quality firm – until they entered administration.

The consequences of ISG’s failures are devastating: at least £700 million is owed to their supply chain and 2,400 employees have been fired. Suppliers will fold, be forced to make layoffs or both. Projects totalling hundreds of millions of pounds have been stopped, from university campus renovations to sports, data and biotechnology centres. According to Building Magazine, these projects may never be completed. A smaller fit-out business asked about taking on ISG jobs said, “you never know what liabilities you’re going to find.” He said it is “highly likely” that ISG has won such jobs without having started any actual work.

The Carillion Catastrophe

Carillion was a British multinational construction firm founded in 1999. By 2016, it was the UK’s 2nd-largest construction firm. Two years after that, it was insolvent. With nearly £7 billion in liabilities, Carillion’s collapse was one of UK history’s most damaging corporate failures. Of its 30,000 suppliers, at least 2,000 were themselves driven to insolvency. For every Carillion employee laid off, three more within its supply chain lost their jobs. According to some sources, the losses have reached as high as 15,000, with another 5,000 still to manifest.

Carillion was a FTSE100 traded firm. It was a ‘blue-chip’ company, a term the company and others used routinely in reference to it.

But a 2018 parliamentary report into Carillion’s failure called its business model “a relentless dash for cash”. The mystery, according to the report, “is not that it collapsed, but that it lasted so long.” The remarks at the end of the report’s summary are even more revealing: “Carillion became a giant and unsustainable corporate time bomb in a regulatory and legal environment still in existence today. […] Carillion could happen again, and soon.”

The Illusion of ‘Too Big To Fail’

It’s not just the largest companies that fail, although the notion of a firm being ‘too big to fail’ is nonsense. The Jeff Bezos quote earlier in this piece comes from a November 2018 all-hands meeting in Seattle. In addition to his comments about Amazon going bankrupt, he said Amazon was not “too big to fail”. Amazon is a conglomerate which earns half a trillion USD a year. It is the 2nd-largest company in the world by revenue and the world’s second-largest private employer (with 1.5 million workers.) If its founder and CEO says it is not too big to fail (and he would know), then no company is too big to fail.

The phrase ‘too big to fail’ was popularised during the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008. At the time, the phrase was mostly used to describe banks so large that their bankruptcy would devastate financial markets to a degree never before seen.

Today, the term ‘too big to fail’ has taken on a new meaning, one outside of its association with the GFC and subprime lending. Today, people use it to describe companies that appear so big they are somehow (and not by government action but by less practical methods) innoculated against insolvency.

“Chill dudes. We’re too big to fail.” (Image courtesy of The Times-Mail.)

It is not a political notion. The idea that a company is granted some protection against the usual market vicissitudes just because it earns a certain amount is unsound. Size cannot forecast whether a firm will survive or will fail.

On 3 September 2024, Aqualux, a Hinckley-based manufacturer and supplier of shower and bathroom products, fell into administration. Aqualux employed 24 people at its Leicestershire base. The firm had maintained a good standing among its suppliers for 44 years. After administration, 18 people lost their jobs.

Big companies fail. So do smaller ones. So do scrupulous ones. So do the dilligent, the meticulous, the moral and the reputable.

The Oldest Firms Crash (and so do the Youngest)

A company’s age no indicator of its resilience. ISG had been operating for 35 years when it failed, and Carillion for 25. But retail chain Wilko entered administration in August 2023 after trading for nearly a hundred years. For its entire existence, it was a family chain. By the end of 2022, it had an annual turnover exceeding £1.2 billion. At its peak, Wilko operated 408 physical stores and employed 12,500 people. When rescue deals failed in September 2023, all those stores closed, and all the employees lost their jobs. Reports at the time didn’t blame its downfall on a single person. Some comments from outside the firm even praised the firm and its operating practices.

Homeware and clothing retailer M&Co, a company in business since 1843, failed in December 2022. All 170 stores closed, and more than 1,900 people were left unemployed.

Debenhams, one of the UK’s oldest department stores, was liquidated in May 2021. At the time, it had been trading for 243 years.

No Industry Is Safe

Companies in every sector fail. British Steel was a steel manufacturer and supplier servicing almost every industry in the UK. At its peak it had 5,000 employees, with four times as many in its supply chain. It had a positive reputation, which it had long cultivated and was known for paying customers in a timely fashion. British Steel had good annual revenues (it made over £2.7 billion the year before its collapse). None of these factors, nor multiple refinancing attempts, shielded it from the instability that upended it in 2019.

The Rate and Number of Insolvencies Continues Growing

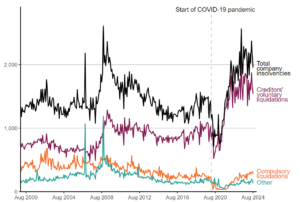

Insolvencies this year reached a high not seen since the start of the 2008-09 GFC. Over the last 12 months, 1 in every 180 UK-registered companies became insolvent. The number of company insolvencies is higher today than during the COVID-19 pandemic. Closures continue to increase. Since Jeff Bezos made his November 2018 remarks quoted earlier, more than 110,000 UK companies have been declared legally insolvent.

Recent insolvency trends from August 2000 until August 2024. (Image courtesy of The Insolvency Service.)

As Bezos said at the November 2018 meeting, the most successful company should be fortunate to measure its lifespan in decades rather than centuries. Companies can last centuries, he said. But to do that requires managing risk. And it requires awareness of certain cognitive fallacies.

Irrationality is destructive; sound reasoning is protective

People whose customers have never paid late, or those with customers they believe to be high-quality and stable, often attribute strength to those customers which is illusory. It is a mirage.

It is a psychological fallacy to assume otherwise. To look at a company’s size, age, industry, reputation or market dominance, to use terms like ‘blue chip’ as if they have any predictive value is sophistry. It is self-deceptive. It can be harmful to the point of ruination. To look at anything a business has done in the past, anything it says it will do in the future, or any other similar benchmark as predictive is irrational.

Successful trade yesterday has no bearing on successful trade tomorrow. Because a customer has always paid on time, does not mean they’ll pay on time next time. They may. They may not. They may not pay at all. They may not be able to pay at all.

The philosopher and statistician Nassim Taleb illustrates this thinking in his book The Black Swan with a parable about a turkey. A farmer feeds a turkey daily. If the turkey thinks as humans frequently do, it will expect to be fed the next day, the day after, and so on. The turkey doesn’t know it is being fattened for slaughter. Only when the turkey is about to be killed will it have what Taleb calls “a revision of belief.”

If a business owner wants their firm to continue without coming to a harsh “revision of belief”, it is vital to understand the futility of prediction. Nothing that has happened in the past can be used as a portend.

Don’t just excise this type of thinking from your mind. Recognise it. In the words of Warren Buffett, “The best way to minimise risk is to think.” Act against these assumptions, but recognise them first, or they’ll creep in again in different forms. They are easy to form and hard to defeat. But they are assumptions. They are beliefs without proof or evidence.

There is no factor that you or anyone else can use to determine if a business will stay afloat or go bust. There is no secret formula, no cloak of invincibility. The only reaction, then, is to manage risk. To protect your business against the myriad of problems that come with customer defaults.

The Best Defence: Trade Credit Insurance

There are plenty of mechanisms by which you can manage risk to safeguard your company. If you deal with other firms, the best of these is trade credit insurance.

Every business – any business – can fail. Dispense with models and bromides alike. Without trade credit insurance, you’re jumping from a plane without a parachute, hoping you’ll land safely. You won’t.